Every good story needs a villain, whether it’s a physical or a metaphorical villain.

Name:

If you really want your villain to stick out, give him or her a good name. It should be something that strikes a chord with the reader, something that fits with the story. It can be mundane or it can be unique, but it should still fit.

A lot of villains will have an alias, but be careful when using these. There are two main types of aliases:

- Epithet: These aliases aren’t actual names and can be tricky to master. “The Dark Lord” is really overdone and stuff like “The Annihilator” is just…lame. Then there’s also nicknames like “scarface” that have a specific story behind them. If you give your villain a name like this, there should be a reason for it.

- A Name: Some villains have a fake name or two. They can use it in their daily life to get around without notice or they can be known as the villain under this name. Voldemort reigns under that name and not his legal name, Tom Riddle. But he also had a reason for choosing Voldemort (it was an anagram of his real name).

The name should match the setting and time. If your villain was born in America during the early nineteenth century, his or her name should be relevant to that time and place.If you want the name to have a meaning that matches the character, do some research. Using this method is a bit harder because if you want the name to have a specific meaning, it still has to match the setting, time, and possibly the background of the character. However, in worlds other than our own, you can play around with this as much as you want.If you want your villain’s name to sound like the character’s personality or appearance, try naming your characters with alliterations before you settle on a name. For example: Sly Severus, evil Elvira, ripped Rocky, etc. You can also make the name sound similar to a certain aspect of the character, such as Hannibal Lecter, or you can use a pun within the name.But then you also have the mundane and common names that end up being memorable such as Annie Wilkes and Michael Myers.Background:

If your villain is an actual character, he or she will have had a childhood (if the character is not a child). Your character’s upbringing it vital. While your readers do not have to know everything, it helps the writer to know as much as possible about his or her characters to write them accurately and in character.

The background of your villain may establish fears or reluctant behavior. It could even be the source of anger or revenge.

Personality:

Your villain can’t be a stock character. It’s boring and it’s lazy writing. Your character needs vices, virtues, quirks, and morals. The villains need a personality too.

Think of your villain’s background to establish personality and use your villain’s personality to establish how he or she carries out evil deeds. If your villain is violent, he or she may torture other characters. If your villain is charming and persuading, he or she may use the psychological approach to strike fear or hatred.

Traits of Effective Villains (2)

Morality:

All villains will be corrupt in the eyes of the opposing force. To understand what makes a great villain, you must understand that morality is the key to your villain.

Establish the Morality: If your story takes place in another world, another culture, the past, or the future, the morality will be different from what it is in your culture. Either research the culture you’re writing about if it is a real culture or make a morality scale if you’re writing about a fictional culture.

Moral Developments: There are three levels of moral development and six stages within those. The idea behind this theory of moral development is that morality continuously changes throughout life. The same should be true for your characters, especially your villain. You should know all about your villain’s morality and how they got there. When filling out character questionnaires that involve moral questions, think more about why your villain would give that answer than the answer itself.

Level One, Preconventional:

- Stage One: The first stage is obedience and punishment. Those in this stage obey rules to avoid punishment. This stage is most common in children, but may occur in adults as well.

- Stage Two: The second stage is individualism and exchange. Those in this stage base moral decisions on whether they get something out of it or not. Individual needs are considered above all.

Level Two, Conventional:

- Stage Three: The third stage is interpersonal relationships. Those in this stage fill expectations for how they are supposed to act. The “goody-two-shoes” personality is common in this stage and moral decisions are based on how those choices will affect relationships and social expectations.

- Stage Four: The fourth stage is maintaining social order. Those in this stage consider society as a whole while making moral decisions. Decisions are based on what follows the law and respects authority.

Level Three, Postconventional:

- Stage Five: The fifth stage is social contract and individual rights. Those in this stage recognize differing opinions and values and base morality on the majority of what society agrees on.

- Stage Six: The last stage is universal principles. Those in this stage base decisions on their own morals and ethics even if it goes against the law.

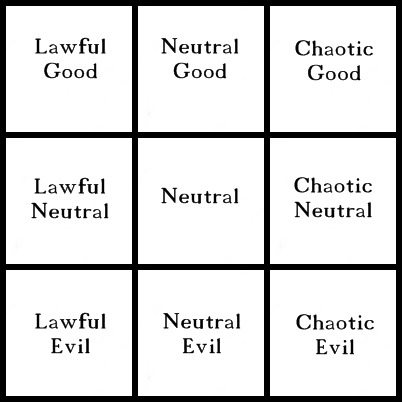

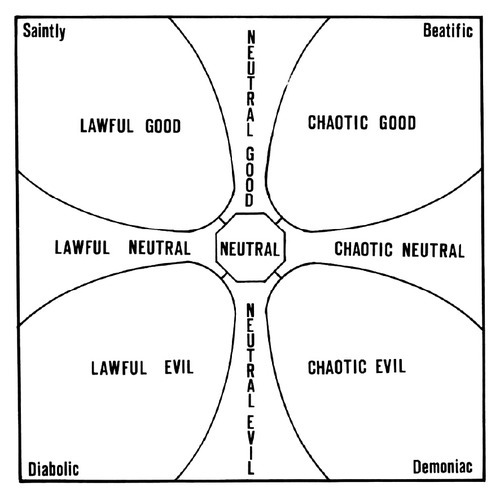

The Nine Alignments: If you know anything about D&D, you probably know about the nine alignments. Or if you known about the alignment meme, then you know about the nine alignments.

The Lawful: Lawful characters are honorable to their values whether those values are ethical or not. They believe everything has a set of rules and that those rules should be followed no matter what. Lawful characters put the needs of the group in front of the needs of an individual. However, these characters may be small minded and stubborn to change. For example, Hank Hill from King of the Hill is a lawful character because he greatly respects authority, the law, the government, and a hardworking person. Another character, Lucky, who is from the same show is also a lawful character because he has a set of personal values and morals that he follows, but they differ greatly from Hank Hill’s morals and values.

- The Lawful Good, “The Crusader”: The lawful good character is essentially a saint. These characters act how one is expected to. Serving justice is a main priority of these characters, but so is helping those in need and following a set of morals or values. Castiel from Supernatural would be considered this type of character when he makes his first few appearances. Other characters include: Batman, Indiana Jones, and Captain America. More Information

- The Lawful Neutral, “The Judge”: This character strongly believes in the law, honorable values, and a personal set of morals. These characters are disciplined and strictly adhere to the law to maintain order. The moral consciousness of these characters is neutral in regards to what the law or tradition calls for. For example, someone may feel as though same-sex marriage is wrong due to their religion, but he or she may also agree that religion should have no say in government affairs and will therefore be in favor of same-sex marriage as a legal bonding. More Information

- The Lawful Evil, “Dominator”: These characters follow their own set of morals, values, and ethics no matter what the law is. They work around the law and find loopholes, even when taking instructions from authority. These characters are selfish and do not care for the rights or freedoms of others. Rules are important to these characters, but the consequences of harmful laws are not as long as they do not affect the character. These characters are often tyrants and rulers. More Information

The Chaotic: Chaotic characters have freedom and flexibility, but reckless. The “rebellious teenager” is a typical chaotic character, as they stand up against authority and prefer personal freedom. However, these characters may also be egotistical and irresponsible. They are more likely to make mistakes because they think too fast and disregard others. These characters do not believe in coincidence and they believe the law is meant to be broken.

- The Chaotic Good, “Rebel”: These characters listen to their gut and their conscience. These characters are good in nature and do not let others influence their actions. While these characters do what is right and good for social improvement, they disregard the law, the rules, and societal expectations. More Information

- The Chaotic Neutral, “Free Spirit”: This character is similar to the chaotic good, but is more about the individual than the group. These characters are promoters of freedom and work with those who happen to share the same values and motives. While these characters are most often disorganized, they may have a main goal in mind. More Information.

- The Chaotic Evil, “Destroyer”: These characters are selfish and will do anything to get what they want. They are often violent, unpredictable, and have no regard for the lives or freedoms of others. These characters are considered the quintessence of evil. More Information.

The Neutral: Neutral characters are a balance between lawful and chaotic. This is the yin and yang of morality. Neutral characters believe the forces of good and evil must work together.

- The Neutral Good, “Benefactor”: These characters are kind, generous, and do all they can to benefit the world. These characters have no favor for or against laws, rules, guidelines, or tradition. More Information

- The Neutral, “Undecided”: These characters do whatever seems good and right. These characters are either the balance between all or the absence of all. More Information

- The Neutral Evil, “Malefactor”: These characters do not intend to harm, do not follow rules if it is not beneficial to them, and do whatever they can get away with. These characters think of themselves more than the group. Sawyer from Lost is an example. More Information

Alignment Test (2) (3)

Final Notes: Moral development is not strictly social. There are several factors that influence a person’s morality and psychopaths are aware of morals and the difference between right and wrong, they just don’t care.

Motive:

Your villain needs a motive. You can’t just have some angry dude who wants to take over the world with no explanation.

Here are some basic motives:

- The Needs of the Many Outweigh the Needs of the Few: Some villains have the motive of serving the greater good or serving what they believe is the greater good. These villains work toward a major goal for a group of people rather than an individual.

- Every Villain is a Hero: Some villains are the heroes. In A Song of Ice and Fire, many of the POV characters view themselves as heroes although other characters view them as villains. These villains are more neutral in terms of morality and often fail to see the harm they do. The motive behind these characters is for personal or group needs and morals.

- Everyone is a Hero in their Own Way: These villains like to image of being a hero, but are underlying villains. They parade around as heroes and great people and many believe that they are. Only few know their true nature. Therefore, these characters have the motive of being a hero, but do not care how reckless they are. The version of Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight Rises is this type of villain even though he is dead. A few people knew that he was a villain while the majority of Gotham City viewed him as a martyr.

Off Screen Time:

If your villain only shows up when convenient for the plot and is never heard of again, you might have a problem. What are they doing between appearances? Do they have other enemies or duties to take care of?

If your villain spends all his or her time plotting against your protagonist, your villain will probably have a large advantage when it comes to defeating the protagonist.

Avoid:

Words and Phrases:

- Minions

- Fools

- Weakling

Appearance:

- Wearing all black all the time (unless you have a good reason).

- A visible scar for no reason at all.

- So super sexy that no one can resist his or her evil ways.

- Always looks good no matter what.

Mannerisms:

- Hissing

- Cackling

- Laughing maniacally

Other:

- Let Me Tell You About My Plan: Sometimes this is done well, but most of the time it’s not. When your protagonist is in the grasp of the villain, the villain shouldn’t go on about his or her evil plan in great depth. A quick mention is all you need. The Joker does this really well because it just works with him. He doesn’t have any premise he just improvises and he’s good at it.

- Speeches: I think we’re all sick of villains who gather their minions and then give a massive speech. Again, sometimes this is done well if there is a purpose behind the speech, but other times it’s used as an info dump.

- More Things to Avoid (2)

Why? How?

The most important question you must answer is why this character is a villain. You must answer why this character opposes the protagonist and why this character does what he or she does.

Refer to the points above about morality, personality, motive, and background to map out why your villain became a villain.

But you also have to answer why your villain is a villain to the protagonist. Your villain, if deliberately chasing the protagonist, needs a reason. There needs to be a great need and motive.

You must also answer how this character became a villain. Was it gradual? Sudden? Was there one final event that pushed this character into become a villain?

Sympathize:

Put a hint of doubt in your reader, make them sympathize with the villain. Give them good qualities that are admirable to make your readers and other characters question what they once thought. Put both your characters and your reader in a state of crisis by showing that your villain has humanity.

Make your villain as complex as your protagonist. Make your villain change. Challenge your villain just as you do the other characters. There are no excuses for flat, static, and stereotypical villains.

More resources:

Just another WordPress site