This town in Russia is called Zheleznogorsk.

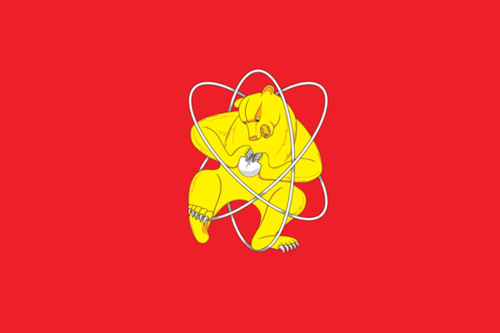

Their flag and coat of arms is a bear splitting the atom.

That is all.

*kicks down door, knocks over end table, vase crashes to the floor*

No that is NOT all, because Zheleznogorsk is really interesting.

It was a secret city, established in 1950 in the middle of Nowhere, Siberia for the purpose of researching nuclear weaponry and producing massive quantities of plutonium, the facilities for which were hidden inside a hollowed-out mountain. It appeared on no maps, and had no census data. Although more than 100,000 people lived there at one point, satellite imagery would have shown only a fairly small mining town. The mountain complex contained 3,500 rooms and three plutonium reactors, which were kept cool by one of the mightiest river in Siberia. The space had been excavated by tens of thousands of gulag slave laborers, who removed more rock from inside the mountain than was used to build the Great Pyramids. Protected under the granite peak of the mountain, these facilities would survive a direct nuclear attack.

No one called it “Zheleznogorsk.” Officially, it was “Krasnoyarsk-26,” which is something like naming a city ‘Arizona-17.’ Residents traveling outside the city called it Iron Town, if they had to refer to it at all. They were under strict instructions never to reveal to anyone the actual business of Krasnoyarsk-26.

And life there was fantastic. People living and working in the secret city received some of the best wages in the Soviet Union. There were sports stadiums, public gardens, a movie theater, and the shortages notorious in the rest of the USSR were unknown. The best nuclear scientists in Russia lived in a sealed-off utopia.

A third of all the nuclear weapons produced in Russia during the Cold War were powered by fuel from Zheleznogorsk. At the time, the image of the great Russian bear ripping an atom apart wouldn’t have seemed very funny at all.

I love the history side of Tumblr

UM, SO. MY GRANDFATHER ACTUALLY BUILT THIS TOWN, AND HELPED RUN IT FOR MANY YEARS.

He was a (Jewish) university student with a degree in electrical engineering (he volunteered for military service after his dad was killed in WWII and served during wartime even though he was underage and medically prohibited from serving in the military. He faked his papers and went to “avenge his dad” at 17.)

Anyway, after the war he started uni and graduated with a Master’s in engineering 5 years later, in the early 50s. He was then due to receive his mandatory 3 year assignment (as all Soviet uni students did – higher education was free, but you spent your first three years working wherever they sent you), except instead he was tapped by the KGB, for reasons he wasn’t clear on until his death (he has several relatives declared Enemies of the State during Stalin’s purges, and he was Jewish, so not exactly a prime candidate for top secret work.)

Anyway, they sent him to the middle of nowhere, Siberia, where he lived in a tent in the wilderness with a few other guys, and was in charge of building a city. It took over a year before any of his immediate superiors even moved out there, because it was literally in the middle of a snowy forest. My grandfather was in charge of making a city plan, laying roads, building houses, building the nuclear facilities, all of it. Eventually he and tent-mates moved into temporary houses, and then eventually real houses.

He wasn’t a nuclear scientist, he worked on the logistical side of the city, but he continued to run it until he left. They were in charge of all the infrastructure, including work inside the nuclear reactors. He was involved in an accident once, where a “minor” bomb exploded and knocked down a bunch of protective walls and he was in the hospital for a while, with radiation poisoning among other things.

Some of the most gruesome stories my grandfather used to tell were about supervising the prisoners who were extracting rock from the mountain. It was not only slave labor, it was also a death sentence. They were not given safety equipment and the rock dust would quickly settle in their lungs. Since they had nothing to lose the prisoners did everything to prolong or fuck up the process of carving the mountain. They’d set clever traps that would only be discovered months later and delayed construction. To be clear, tampering with this system, or with the fates of the prisoners, was considered treason, punishable by death. Similarly, any serious fuck up in constructing the town and facilities my grandfather was in charge of, would have similarly meant a conviction for treason and a potential execution for my grandfather.

Eventually on one of his vacations back home my grandfather met my grandma, they wanted to get married but she had to get security clearance before they let her move to a secure zone. This was actually a huge problem, and my grandparents lived apart for months when my grandpa had to go back to work and my grandma wasn’t allowed to join him. You see, my grandmother, who was 11 when WWII broke out, had to account for every single day during the war to prove she had actually been in a concentration camp the whole time and hadn’t been aiding the Germans and their allies (my grandmother was Jewish). If even one day was unaccounted for she’d be considered too risky to let into a place like Krasnoyarsk-26. She had to produce documents, witnesses, etc.

Eventually my grandparents were reunited, and life in Krasnoyarsk-26 was indeed pretty awesome. They had everything, no expense was spared. My grandmother, who had a teaching degree, became the teacher of the small school they eventually established for the children of the residents.

Probably my favorite story is how my uncle was born. My grandmother’s relatives obviously didn’t know anything about where she was, but she did write letters and tell them she was pregnant with her first child (she was also the firstborn, so it was the first grandchild for the family). Her mother, my great-grandmother, insisted on coming over to help her during and after the birth, as otherwise it was just my grandparents living on their own in their little apartment, and my grandfather would obviously not get any paternity leave.

This was strictly forbidden, no unathorized people were allowed into the town, and my grandfather wrote to his mother-in-law telling her as such. This did not even slightly deter my great-grandmother, who, among other things, managed to pull 5 little girls through Nazi concentration camps all on her own. She completely ignored my grandfather, packed her bags, went to Krasnoyarsk (the actual, non-secret city) and started asking questions about this mysterious Krasnoyarsk-26 and where she might find it. Eventually she actually managed to figure it out and showed up at the gates of Krasnoyarsk-26 asking for my grandfather. Since he was well known and well liked my grandfather was alerted to deal with the problem, and my great-grandmother made it clear to him that she wasn’t leaving. He had to sneak her in through a secret passage, basically making a long journey in the snow, and eventually illegally brought her into the city. This is probably my favorite story about my great-grandmother.

Eventually my mom was born, and as a child started having health issues. She got sick a LOT and the doctors told my grandparents that she wouldn’t survive another Siberian winter. My grandmother took her back to the south of Ukraine, to live with family, and my grandfather had to find a way to quit his job and join them. You have to understand you didn’t just quita top secret nuclear facility in the Soviet Union. No rules applied here, there were no workers’ unions. You worked there until your services were no longer needed.

My grandfather explained the situation to his superior, and his superior literally pulled out a map of the Soviet Union and said “point to any place on this map and I will find a sanatorium for your wife and children where they can live as long as they like, at the state’s expense, and enjoy every comfort and top notch medical treatment. We can do that for you, but you have to stay here.”

My grandfather refused and said he wouldn’t stay without his family, and his family couldn’t live here anymore, so. They actually eventually did let him go! He counted himself exceptionally lucky.

And then of course when he came home to Ukraine and was reunited with my grandmother he found that because the work had been top secret, it was like his record didn’t exist, and antisemitism in the real world was so severe that no one would give him a job as even a lowest level engineer. He spent months going to interviews, sending his paperwork everywhere and trying to cash in every favor he could just to get any kind of work. Eventually a friend from uni set him up somewhere, with a lower wage and a lower level position than he deserved going purely by his years of experience, nevermind the kind of work he actually did.

I only found out about all this in bits and pieces, and the majority of it started making sense in my head when my grandfather started sharing more, closer to when he died. I actually had no idea about any of this until I joined the military and became an intelligence officer. My family always used to laugh or not get why I couldn’t tell them things, but my grandfather suddenly started displaying a lot of sympathy and understanding for my position.

“There are secrets I signed my name to that I’ll never tell anyone,” he used to say. And i’d say “but grandpa, it’s been 60 years! It’s all been declassified, besides!” And he’d say “that doesn’t matter. I signed my name and I gave my word. I can talk about what daily life was like, but I’ll never talk about happened in the classified facilities. Not even when they make shows about it on television. I’ll never betray the promises I made.”

One part that was super fun/surreal though was comparing classification and information security protocols with my grandpa. “Oh did you do that as well? How interesting!”

Just another WordPress site